Case Study:

How sitcoms guide timing, structure and building empathy?

Our brain is a prediction machine, and sitcom plays with that in a gorgeous way. Sitcom is basically a cognitive lab: timing, connection and structure at play — shaping what we feel, and what surprises and stays. (Neurodesign, anyone?)

Challenge:

INT. STRUCTURE OF SITCOM – COLD OPEN

Sitcom is one of the most brutally difficult formats of storytelling, and Friends is one of the best examples of glorious writing to examine. (My opinions, or a universal truth.)

I was invited to break down one episode of Friends – to the nuts and bolts – to see the architecture of an excellent (disgustingly well-written) story. A good sitcom is sharp, empathetic, opens new perspectives, and takes a bold stand. I wanted to know how the structure communicates the premises, the main statement.

Educational analysis of FRIENDS S05E22. Credits: Bright/Kauffman/Crane.

Why this matters: story plays with our brain’s built-in prediction mechanism — Plant → Reminder → Payoff. That’s why we love it.

#Keywords: sitcom, premises, comedy, dramaturgy, main statement, Friends

Story, especially sitcom, is basically a controlled prediction error machine: it plays with the Plant–Reminder–Payoff — the learning loop the brain is wired for.

Approach:

Breaking Down the Structure

A typical sitcom episode is about 22 minutes. Each episode has a central storyline (A-plot) with the secondary storylines (B- and C-plots), which reflect the main storyline.

The architecture typically is:

Teaser or Cold Opening (minutes 1–3)

The Trouble (minutes 3–8)

The Muddle (minutes 8–13)

The Triumph or Failure (minutes 13–18)

The Kicker or Sunset (minutes 19–21)

You can see the analysis of the architecture below.

The Premise and Empathy:

FRIENDS | “The One With Joey´s Big Break”

USA 1999, Bright/Kauffman/Crane Productions. Aired in the US on May 13, 1999, in Finland in 1999 on MTV3. Season 5, ep. 22. Story by Shana Goldberg-Meehan, teleplay by Wil Calhoun.

(Yes, I’m a geek.) I wanted to share the architecture, so we can admire the genius work of Bright/Kauffman/Crane Productions. The episode is analyzed with Hellerman (2020) framework.

Of course it’s not just about Friends – it’s a about understanding how hidden structures shape what we feel, remember, and connect with, and how comedy can bring our deepest things to surface.

Firstly: the episode’s composition, causality, and multi-plot dramaturgy are crafted with precision. Especially striking is the use of the ‘plant–reminder–payoff’ technique, echoing Chekhov’s famous rule: if a gun hangs on the wall in the first act, it must be fired before the last.

Deliverable

A clean beat map and five takeaways you can apply anywhere.

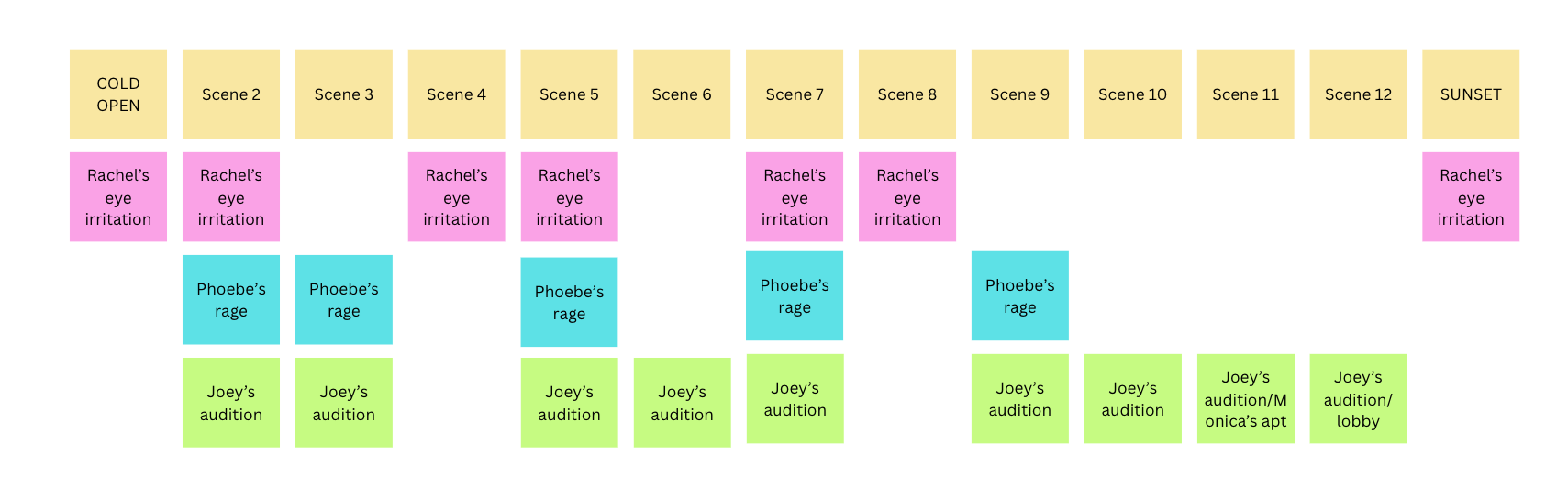

Beat Map How to read: Horizontal = time, Vertical = Plots. Pink = A-plot, Teal = B-plot, Green = C-plot.

Beat-map: Yellow = Scene beats (timeline / rhythm): Pink = A-plot (main premise): Teal = B-plot (supporting tension): Green = C-plot (supportin tension, can also be running gag). Read horizontally for timing, vertically for interweave.

Analysis: The Premise is what the storyteller wants you to feel.

In sitcom, like any other good storytelling, the premise is partly subjective: it often holds a personal insight for the writer while leaving space for multiple interpretations. A well-crafted episode builds around the premise, allowing viewers to reflect their own perceptions.

Examining the A-, B-, and C-plots shows how the premise connects to everyday life—our fears, dreams, and unintended honesty—where truth emerges despite attempts to suppress it.

Insights

The analysis confirmed the high quality of Friends scripts: they do explore the premise from many angles without reducing it to a single claim, but instead leave it as an open code—an idea, or even something unspoken.

Takeaways for Design & Strategy – Comedy Is Empathy in Disguise

(I’m in awe, and only slightly devastated. Who wouldn’t want to write like that?)

Comedy shows how well structured story can make us laugh and cry. (That’s empathy.) Humor reveals hidden truths — and the unsaid is powerful.

Multiple storylines can align around one premises and weave a beautiful net of perspectives.

Consistency builds trust – and surprises. Plant–reminder–payoff.

Silence speaks. The unspoken can matter the most.

And: Everything is storytelling.